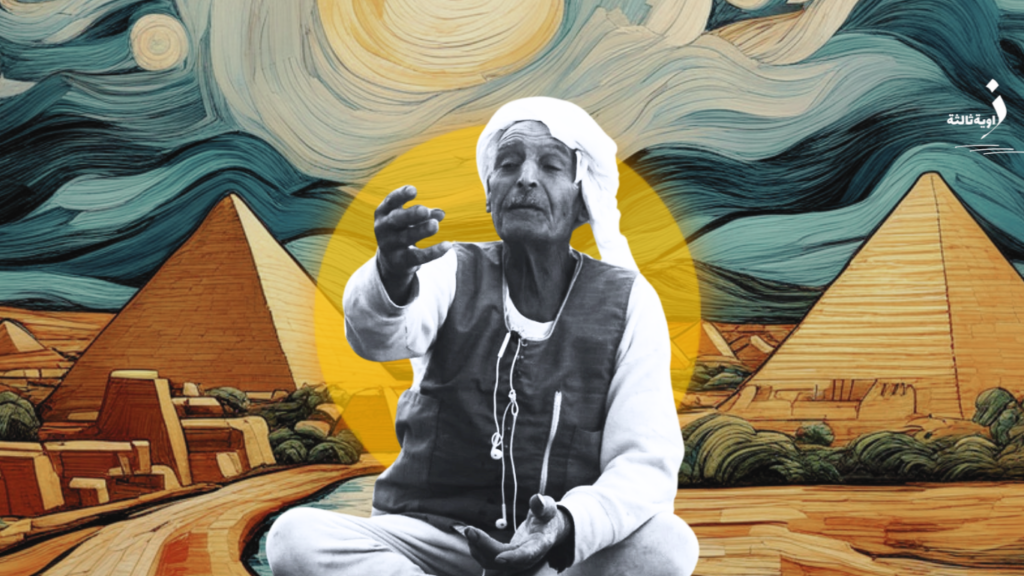

“I had intended to establish an irrigation well for agriculture this year, but the inspection by the Ministry of Irrigation was rejected. Now, all I have left is to cultivate leafy vegetables due to the fear of water shortages, a situation prevalent in most village farms,” said Abdul Raziq Omair, a farmer from the “Zawiyat al-Naggar” village in the Qalyubia Governorate. He opened up about the water scarcity crisis facing farmers after the failure of negotiations regarding the Renaissance Dam.

Negotiations between Egypt and Ethiopia have failed over a period of 12 years, in six complete attempts. Each time, the parties announced reaching an impasse, leading to the end of negotiations without solutions, according to Abbas Sharaqi, a professor of geology and water resources at Cairo University. The negotiations went through nine stages from 1995 to 2020, then were frozen from 2021 until they resumed in four rounds during 2023 and early January of the current year. However, all attempts were declared unsuccessful.

According to experts, if the dam filling process continues, Egypt will lose more than a quarter of its share of the Nile water, which amounts to 55 billion cubic meters. This is insufficient considering the population has exceeded 105 million Egyptians. Additionally, about one-third of its estimated 10 million acres of agricultural land will be destroyed since each acre requires 5 to 6 thousand cubic meters of water. On a direct level, Egypt will lose around a million jobs and over 1.8 billion dollars, including 300 million dollars from electricity production and sales. Egypt will also spend about 50 billion pounds annually to compensate for the Nile water shortage through desalination, equivalent to approximately 12% of the state budget.

Abdul Raziq Omair is one of thousands of farmers suffering from water scarcity in Egypt, exacerbated by climate change, which could lead to significant crop losses. He states, “The village has many crops, including wheat, among others, but small landowners cannot bear any losses. Therefore, their safe option is to cultivate vegetables that require a short cultivation cycle, especially with the continuous state statements about water scarcity and fear of sudden government decisions.” According to him, many farmers in his village initially turned to digging wells for groundwater use as an alternative for irrigation, but they retreated after the government tightened penalties for unauthorized well digging. Instead, they preferred cultivating vegetables for quick sale. He also believes that wells are not entirely safe due to the presence of a sewage drain in the village, exposing them to the contamination of groundwater with sewage water.

In December of last year, the Cabinet approved amendments to some provisions of the Water Resources and Irrigation Law issued by Law No. 147 of 2021, aiming to strengthen penalties and criminalize unauthorized well digging. The amendments stipulate that those who dig wells without a license from the Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources shall be punished with imprisonment for no less than one month and a fine of no less than 50,000 pounds, not exceeding 500,000 pounds, or one of them.

Government Acknowledgment

In August of last year, Egyptian Minister of Irrigation Hani Sewilam, during his participation in the Water Week in the Swedish capital Stockholm, admitted that Egypt is approaching the water scarcity line, with an estimated 500 cubic meters per person annually. He considered that the solution lies in expanding the use of water desalination for food production to address population growth, provided that water units are used optimally to achieve economic feasibility. He emphasized the importance of expanding the use of modern technology and renewable energy in desalination to reduce costs.

According to the General Authority for Statistics, Egypt’s share is 60 billion cubic meters annually, mostly sourced from the Nile River, in addition to very limited quantities of rainwater and deep groundwater in the deserts. In contrast, Egypt’s total water needs reach around 114 billion cubic meters annually, compensated through the reuse of agricultural drainage water, surface groundwater in the valley and delta, as well as importing food products from abroad, accounting for 34 billion cubic meters annually. Agricultural water use represents the largest portion, reaching about 65 billion cubic meters out of the total water usage in 2018.

Unexpected Decisions

Simultaneously with the Renaissance Dam negotiations, statements about water scarcity have led to several changes in the lives of farmers, notably due to parliamentary amendments allowing the prohibition of cultivating water-intensive crops such as rice and sugarcane in April 2018.

The amendment allows the Minister of Agriculture and Land Reclamation, in coordination with the Minister of Water Resources and Irrigation, to designate areas for planting specific crop varieties to rationalize water consumption, prevent interbreeding of strains, and preserve the purity of seeds and varieties. The amendment imposes fines of no less than three thousand pounds and not exceeding ten thousand pounds per acre on violators, with the removal of the violation at their expense. Violators may also face imprisonment for a period not exceeding six months.

In Kafr Ghatati, Giza Governorate, the situation is not much different from the village of “Zawiyat al-Naggar.” Abdelkader Shhata settled for planting onions, despite abstaining from it the previous year due to incurred losses. However, the increase in its price tempted him and others to cultivate it, especially since it is not a water-intensive crop. Abdelkader says, “The year before last, I lost nearly 50,000 pounds due to the decrease in onion prices. Therefore, I limited myself to cultivating leafy vegetables only. But with the price increase, I decided to plant onions this year and made profits despite the suspension of exports.”

Abdelkader adds that small landowners in the village turned to cultivating “turnips” despite being labor-intensive and requiring continuous irrigation. Still, it is a surface irrigation that does not consume much water. The demand for turnips is significant during Ramadan, making cultivation during this time profitable, especially for small landowners. He emphasizes that frequent statements by officials about the water crisis and accusing agriculture and farmers of being the main consumers have instilled fear among farmers, making them think more than once about choosing the crop to cultivate.

Absence of Agricultural Guidance

Regarding the absence of agricultural guidance, Ahmed Gala, an agriculture professor at Ain Shams University, stated that the fundamental solution lies in agricultural education and training farmers on modern irrigation systems. He pointed out three available solutions to the irrigation water crisis, as it is the primary consumer of Egypt’s water share. The first is the use of smart irrigation and modern irrigation systems instead of traditional systems for all crops. The second solution involves developing new crop varieties that are not water-intensive or can tolerate salinity, such as dry rice. The third solution is the reuse of agricultural drainage water, all of which can save a significant amount of water and benefit farmers.

Gala emphasized that all these solutions are mere “paper solutions” unless farmers are trained on them and the concept of smart agriculture is disseminated. Continuous training and a greater role for agricultural guidance are necessary, as it used to be before.

Regarding lands exposed to salinity due to their proximity to the sea, Gala said that achieving smart water use would allow large quantities of water, which can be used for flood irrigation of those lands. This approach is beneficial for lands exposed to salinity because of the high salt concentration, making it ideal for rice cultivation.

What Gala mentioned about the absence of education and agricultural guidance aligns with what MP Hisham El-Hossary, head of the Agriculture and Irrigation Committee in Parliament, stated during the committee’s meeting in November last year. He noted that agricultural associations “no longer have a role” and emphasized the need for the active involvement of agricultural associations to meet the needs of farmers, considering the current stage and the strategic interest of the state and political leadership in Egyptian farmers and the agriculture sector in general.

Governorates of Wells

Before 2018, Magdi Mahmoud used to plant rice in his land located in the village of Oweishe El-Hagar, affiliated with Mansoura, before its cultivation was banned. He then turned to wheat cultivation. Magdi says, “Since 2018, not a single acre of rice has been planted in the village, although we did not rely on Nile water for its cultivation but rather on a groundwater well I dug in my land before the decision to ban well digging.”

He adds, ” My agricultural land is located near an irrigation canal, but water does not easily reach it. Therefore, eight years ago, I decided to dig a well to irrigate the three plots that I own”.

Magdi points out that the cultivation of rice is of great importance in the lands of northern Delta because they are exposed to salinity and barrenness. Rice cultivation used to act as a soil wash from salt. The Ministry of Irrigation allowed the cultivation of 182 thousand acres of rice in the Dakahlia Governorate this year, specifying the permitted areas for its cultivation.

Despite the continued operation of the existing well on Magdi’s land, he lives in fear that the irrigation inspection may close the well due to the new amendments to the law. He mentions receiving a warning from the agricultural engineer that the Ministry of Irrigation is monitoring wells in all governorates.

Over the past five years, Egyptian farmers have increasingly turned to digging groundwater wells to secure irrigation water, threatening Egypt’s estimated 7.5 billion cubic meters of groundwater reserves, according to the Ministry of Irrigation’s announcement in 2017. This prompted Parliament to amend the Water Resources Law, making the penalty for well digging without a permit imprisonment for one month and a fine of no less than 50,000 pounds, not exceeding 500,000 pounds.

Giant Projects

Despite the water crisis in Egypt, the government is expanding agricultural projects, including reviving the Toshka Project, also known as the Million and a Half Acres Project, and the New Delta Project targeting 2.2 million acres.

Describing them as “essential projects,” MP Fahti Qandeel, a member of the Agricultural Committee, emphasized Egypt’s expansion in these massive agricultural projects, citing them as a necessity to achieve Egypt’s food security amid the continuous population growth. He added in statements to “Zawia3” that these projects rely on recycling agricultural drainage water. The Ministry of Agriculture has also banned the cultivation of any water-intensive crops in these projects. He pointed out that Egypt is caught between two fires: first, maintaining food security, especially with population growth, and second, the water shortage crisis due to climate change and the Renaissance Dam. In recent years, the government has been trying to efficiently solve both crises, starting with projects to enhance the efficiency of the irrigation network, such as canal lining, modern irrigation methods, and treating agricultural drainage water, including the Burullus Station project and other initiatives. It aims to achieve food security through large-scale agricultural projects.

According to the presidency, the government has undertaken several water treatment projects, the latest of which was in September last year when the Bani Suef station for treating sewage water was inaugurated to be used in irrigating green spaces instead of water suitable for crop cultivation. In March of the same year, the New Minya station with the same purpose was opened. One of the most significant projects in this context is the treatment of the drainage water of the Mediterranean Sea, described as the world’s largest agricultural drainage water treatment station. It is supposed to contribute to reclaiming 456 thousand acres by recycling and utilizing agricultural, industrial, and sewage drainage water.

According to official data, the government seeks to support agriculture amid the water crisis in Egypt. However, millions of Egyptian farmers live in fear of their lands turning barren due to water scarcity or as a result of sudden official decisions that result in irreparable losses.