In broad daylight, on the facades of shops, stands the citizen of Sinai, gazing at some essential products: clothes, detergents, bathing tools, shoes, and more. What’s striking, though, is that they bear the phrase “Made in Israel” and are openly sold on street stalls and inside shops in the city of Al-Arish, the capital of North Sinai. They were previously smuggled through tunnels from Gaza, but now they are sold across the Egyptian borders with occupied Palestine.

Goods and products of Israeli occupation are widespread as a popular trade in the markets of Al-Arish and the border town of Sheikh Zuweid, especially with the increasing interest of traders and citizens in them. These products are promoted through various social media pages and groups, including men’s and women’s shoes and clothing, cosmetics, perfumes, as well as food items like dried milk, shampoo, soap branded “Hawai”, and electric cooking appliances. Egyptian traders buy smuggled goods from Gaza and occupied Palestine.

Israeli occupation goods and products are widely traded in the markets of Arish and the border town of Sheikh Zuweid, especially with the growing interest of traders and citizens. These products are promoted through various social media pages and groups. They include men’s and women’s shoes and clothing, cosmetics and perfumes, as well as food items like dried milk, shampoo, “Hawaii” brand soap, and electric cooking appliances. Egyptian traders buy smuggled goods from Gaza and the occupied Palestinian territories.

Citizens interviewed have stated that they are accustomed to buying these goods not because they are cheaper compared to Egyptian products, but because of their quality. Emad Hegab, a citizen from northern Sinai, specifically points out that they find Israeli occupation products of unmatched quality compared to Egyptian products, which motivates them to purchase them, especially since they are widely available due to large-scale smuggling, facilitated by the Egyptian authorities’ turning a blind eye, particularly the Supply Directorate in northern Sinai, encouraging traders to openly sell them in commercial stores.

He adds, “Food products were the most popular in recent years, especially after the January 25 revolution in 2011. They used to arrive promptly, to the extent that ‘Shamenet’ yogurt would reach us the same day it was produced or the next day at the latest, along with other dairy products. However, after the complete closure of tunnels, smuggling through the borders with the occupied Palestinian territories became the alternative.”

According to the provisions of the new Customs Law No. 207 of 2020, anyone caught smuggling faces imprisonment and a fine ranging from ten thousand to one hundred thousand Egyptian pounds, or both penalties, without prejudice to any more severe penalty stipulated by another law. If the smuggling is for commercial purposes, the penalty is imprisonment for a term of not less than three years and not exceeding five years, along with a fine ranging from twenty-five thousand to two hundred and fifty thousand Egyptian pounds, or both penalties.

Smuggling is deemed to occur when presenting forged or artificial documents or invoices, affixing false marks, concealing goods or marks, or committing any other act aimed at evading all or part of the customs duties due or in violation of the applicable regulations regarding prohibited goods.

In this context, Ahmed Al Azhar, a trader from northern Sinai, notes that all Israeli occupation products used to enter Sheikh Zuweid and Arish through border tunnels with Gaza, and during that period, Sinai was not limited to receiving only dairy products; it extended to tea, coffee, cocoa, chocolate, biscuits, snacks, jams, olive oil, and clothing.

He adds, “After Egyptian authorities tightened their grip on tunnels and completely closed them, the alternative became “suitcase traders” and Palestinian travelers entering from the sector through the Rafah border crossing, along with intensified smuggling operations carried out by tribal members on both sides of the borders, especially in areas like Ras Al-Naqb, Al-Manbatah, and Wadi El-Amro”. This is because these are goods and products of high quality with customers seeking them out and purchasing them despite their high prices.

Iman Al-Kashef, a Sinai resident, emphasizes a particular interest in detergents coming from the other side. She adds, “I don’t care if the quality of Israeli occupation food products is available; what matters to me is the type of detergents. I buy soap from the ‘Hawaii’ brand in large quantities for household use because it’s the only type that has been proven to interact well with the salty water in our homes or those delivered through tanks, especially since most water in Sinai cities is not suitable for drinking or domestic use, and Egyptian or Turkish soap doesn’t work with it.”

According to residents of Al-Arish, “Hawaii” soap remains the best despite its high price. The price of a single soap bar was around 20 Egyptian pounds, which continued to rise to about 60 pounds after the start of the Israeli war on the besieged sector, with travelers and “suitcase traders” from Gaza unable to arrive, and the source limited to smuggling across the borders alone.

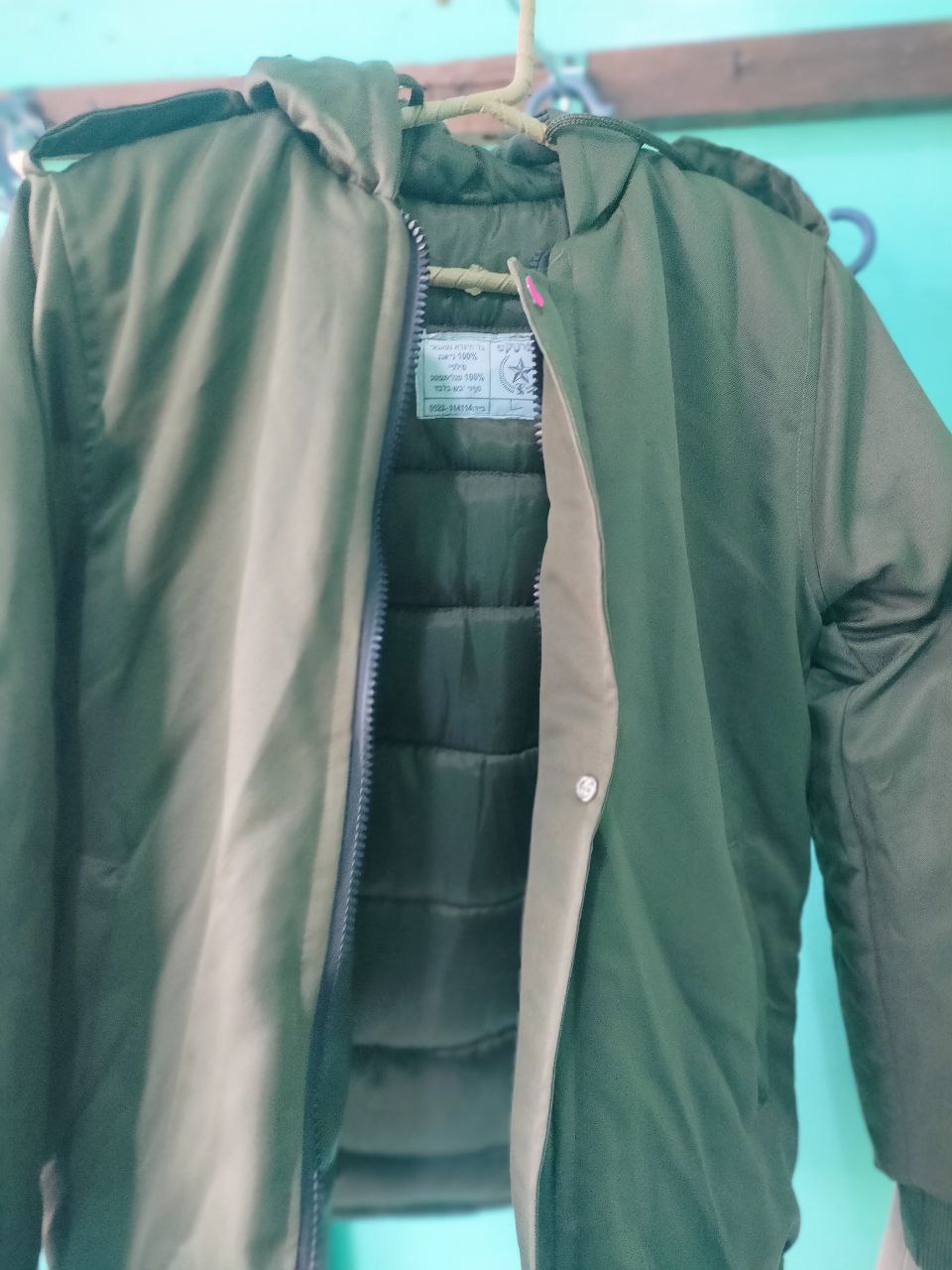

Rahma S., a university student at Sinai University, encountered “Zawia3” during her purchase of similar products at the Jawad market in central Al-Arish. She answered, “Yes, I buy shampoo, conditioner, many cosmetics, and household clothes—especially winter ones—because they are of high quality and are openly sold in many stores, indicating that they are not prohibited.” She adds that the price of a shampoo bottle ranges from 130 to 250 pounds.

The abundance of Israeli occupation goods in some Sinai markets, especially the black market, is not new. According to discussions with some Sinai elders, these goods were prevalent until the late 1980s due to the conditions of war and Tel Aviv’s occupation of the Sinai Peninsula. What remained of these products allowed for their circulation for long periods after the October 1973 victories. This situation persisted until these products gradually disappeared from Egyptian markets in 1995; however, they reappeared with the resurgence of what became known as the “black economy,” represented by trade through tunnels between Egypt and Gaza since 2005. This turned Al-Arish and Sheikh Zuweid into secret black markets for various Israeli occupation products, attracting citizens from urban provinces to purchase them, including some celebrities and artists.

Despite the openness of buying and selling Israeli occupation products, a merchant in Sheikh Zuweid refused to have his products photographed in his shop, saying, “We don’t want trouble with the supply department,” sarcastically adding, “Yes, we buy these products for our homes and needs, but not publicly. If newspapers report what’s happening, we would consider it a crime, but there’s nothing we can do.”

Salem Suwarka, a Sinai trader, states that due to the illegality of selling smuggled products before January 25, 2011, they used to place a “Made in Palestine” label over the “Made in Israel” one to avoid security repercussions, especially since these products bear Hebrew phrases and lack documents proving their legitimate entry into the country through official ports. There are legal procedures taken against any unknown-source goods sold in markets.

He continues, “Today, some traders have struck significant deals on Israeli occupation products, storing them over the past months, with the start of the Israeli war on Gaza, so they can trade in these diverse goods at the prices they set.”

Similarly, Ismail Gouda, a trader from northern Sinai, acknowledges that these products have their customers, and there are well-known shops that only sell them, especially after the relaxation of supply inspections and the interest of supply employees in buying such goods despite considering the prices, as they turn a blind eye to their sale.

He adds, “There are goods displayed under unknown names that are actually Israeli-made, and sometimes products are revealed through very small phrases written in Hebrew or English indicating the manufacturing place, but these are not noticeable to the general public. Recently, there have been discoveries of smuggling modern devices like mobile phones manufactured by the Israeli occupation.”

Gouda points out that the profit margin from selling these Israeli products is not significant due to their smuggled nature, passing from hand to hand, with each smuggler taking a percentage of the profits at each stage. However, the high demand for purchasing them compensates for these expenses through frequent sales, which are much higher than the profits from Egyptian products in any case.”

Responding to a question about why they accept buying these products, he says, “We realize that these Israeli goods and products are smuggled and prohibited from entering and circulating in the country entirely. Still, the authorities’ tolerance, despite the public sale of Israeli products on several streets and markets, encourages smugglers and traders to bring and sell these goods openly during daylight hours without any legal considerations, as the seller knows that there is no authority capable of seizing these goods and initiating cases and violations against them.”

Khalil Abdul Karim, another Sinai trader, does not deny the danger of the unknown source of these products, saying, “There was a famous incident that occurred last Ramadan where a family from Al-Arish was poisoned due to consuming one of the smuggled food products that was spoiled, and no one knew.”

According to our field tour, these products are present on 23 July Street in Al-Arish and have become circulated prominently in the markets, especially in “Jawad Market” and “Gaza Market,” more than Egyptian products, and they receive significant interest from the city’s residents.

Mohammed Bakr, owner of a renowned herbal shop in Al-Arish, says that Al-Arish and border towns have large quantities of these products, but they are not openly displayed; rather, they are stored and kept under customer request. He points out that there is a high demand for them, not only from Sinai residents but also from customers coming specifically from Cairo and Alexandria to obtain them.

Bassam Samri, who displays soap and shampoo products inside his herbal shop on 23 July Street in Al-Arish, adds that the profit margin from selling these products may exceed 50% depending on the customer buying these goods. Alaa El-Belk, a seller at one of the herbal shops, explains that products, especially shampoo and some food items like cashews, pistachios, sandals, and shoes, are usually sold in herbal and hardware stores because they have been known for years to sell these products generally along with smuggled items.

Issa Salman, a trader specializing in clothes and shoes brought through smuggling, says that clothes, especially coats, have special customers from tribal members because they are distinctive in terms of quality and design, as they are not affected by rain. The price of a coat ranges from 1600 to 2000 pounds.

Salman explains that among the goods that are highly popular are sandals from the “Schurch” brand, priced at 3000-3500 pounds, along with sandals from the “Tost” brand and pants made of gabardine, and lighting flashlights usually used by tribal members in land hunting.

Since October 7th last year, Israel has waged a destructive war on the Gaza Strip, which many likened to a genocide, leaving tens of thousands of victims, mostly children and women, and causing massive destruction to infrastructure and a humanitarian catastrophe, leading Israel to face charges of committing genocide crimes before the International Court of Justice.