The Egyptian presidential elections for 2024 concluded with President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi securing a third term. During this time, the Gaza war emerged as a major factor in the electoral process. Sisi interpreted his victory as a rejection of “inhumane war” on the Gaza Strip, especially in the face of “security threats surrounding the southern, western, and eastern borders.” Along the borders with Gaza, the occupying forces waged their war on the sector, which posed threats to the Egyptian side. On the Sudanese border, Egypt became a primary route for Sudanese fleeing the civil war, welcoming around 300,000 refugees. Additionally, Egypt engaged in intense discussions with Ethiopia regarding the management of access to the Nile River waters due to the construction of the Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, escalating regional tensions.

Few Egyptians believe that Sisi’s choice represents the Egyptian military needed in times of crisis, as described by activists.

The observer in the Egyptian scene, prior to the Gaza war, believes that Sisi and his regime succeeded in turning the tide in their favour after the outbreak of the war. This is especially notable as, according to observers, there was heightened concern about the rising popularity of the candidate Ahmed Tantawi, who managed to gather the required endorsements to enter the presidential race. Tantawi succeeded in mobilising the Egyptian street in his favour and gained unexpected popularity in a short period, in contrast to other candidates who, according to analysts, represented an alternative to create an “ideal” image for the electoral process.

At the same time, external voices expressing anger and rejection of Sisi’s presence escalated, with heated debates in the European Parliament about his regime, portraying it as repressive, particularly in the realm of freedoms. In October of last year, the Parliament unilaterally adopted a resolution urging Egypt to conduct fair and just presidential elections and to cease suppressing the voices of the opposition in the period leading up to the elections. The resolution also criticised Egypt’s treatment of political prisoners, media, opposition, and potential presidential candidates. Meanwhile, the committee responsible for foreign aid in the U.S. Congress studied a proposal to maintain current levels of aid to Egypt, dividing military assistance into four parts and linking it to conditions. The primary condition is the conduct of democratic elections.

Stratfo), an American strategic and security studies centre, published a position paper titled “What Another El-Sisi Term Would Mean for Egypt?” before the elections. It stated that Sisi had lost some support among Egyptian voters due to the worsening economic crisis in the country. However, it is likely that he and his regime would win by a significant margin in the votes, enabling them to implement the policies promised during his third term. These policies include potentially painful reforms aimed at achieving economic stability, under the pretext of obtaining a popular mandate through the number of votes he receives, signalling a decisive victory before the elections commence.

In an article for The Washington Post, the writer and analyst Claire Parker discussed that Sisi and his regime were betting on Egyptians and foreigners tolerating internal suppression practices, the contraction of civil rights, and poor economic management, as long as they are assured that Cairo will remain calm and stable in the region torn by unrest. This has been the cornerstone of Sisi’s governance since coming to power in 2014. This rationale was once again put forward as an alternative electoral program following the outbreak of the Gaza war, hinting at threats to the region’s stability if matters escalated. Therefore, the international community was urged to accept his continuation to ensure stability and allow Cairo an active role in ending the war.

|

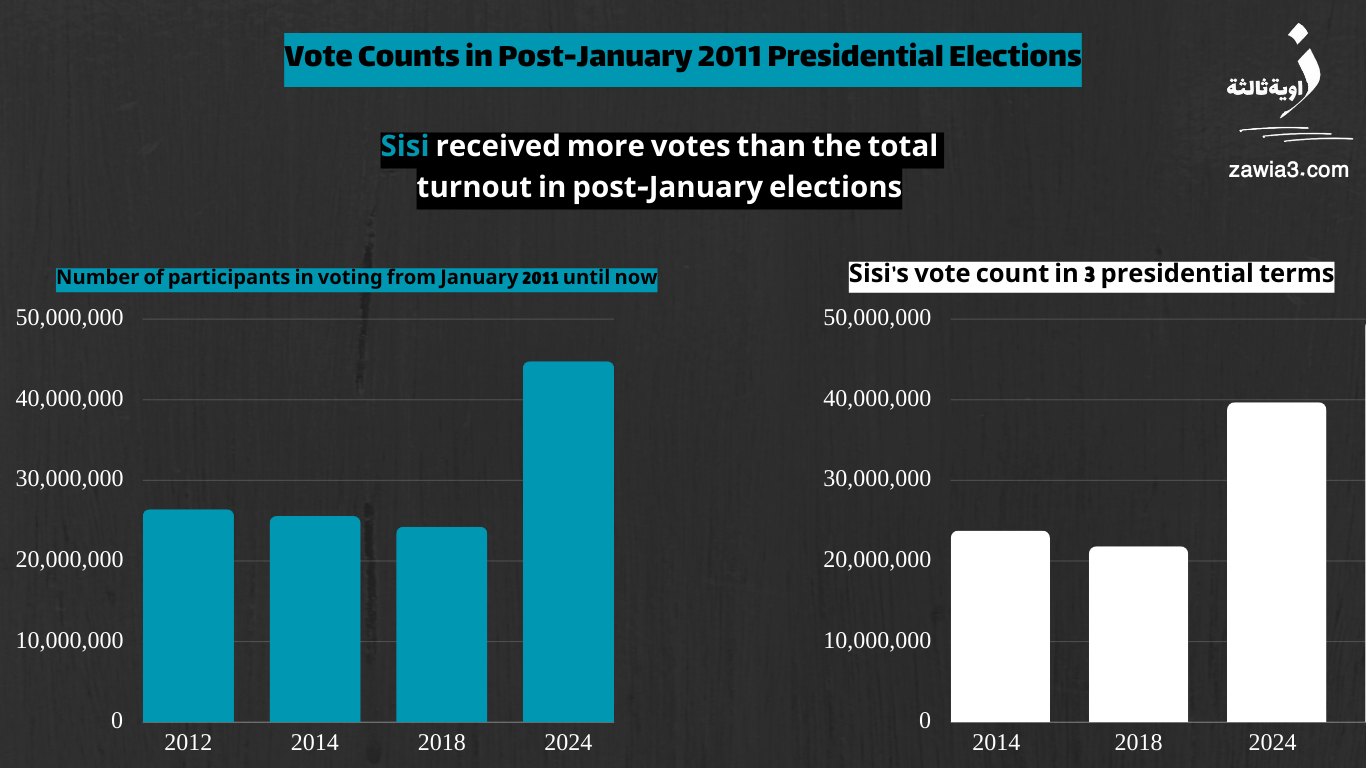

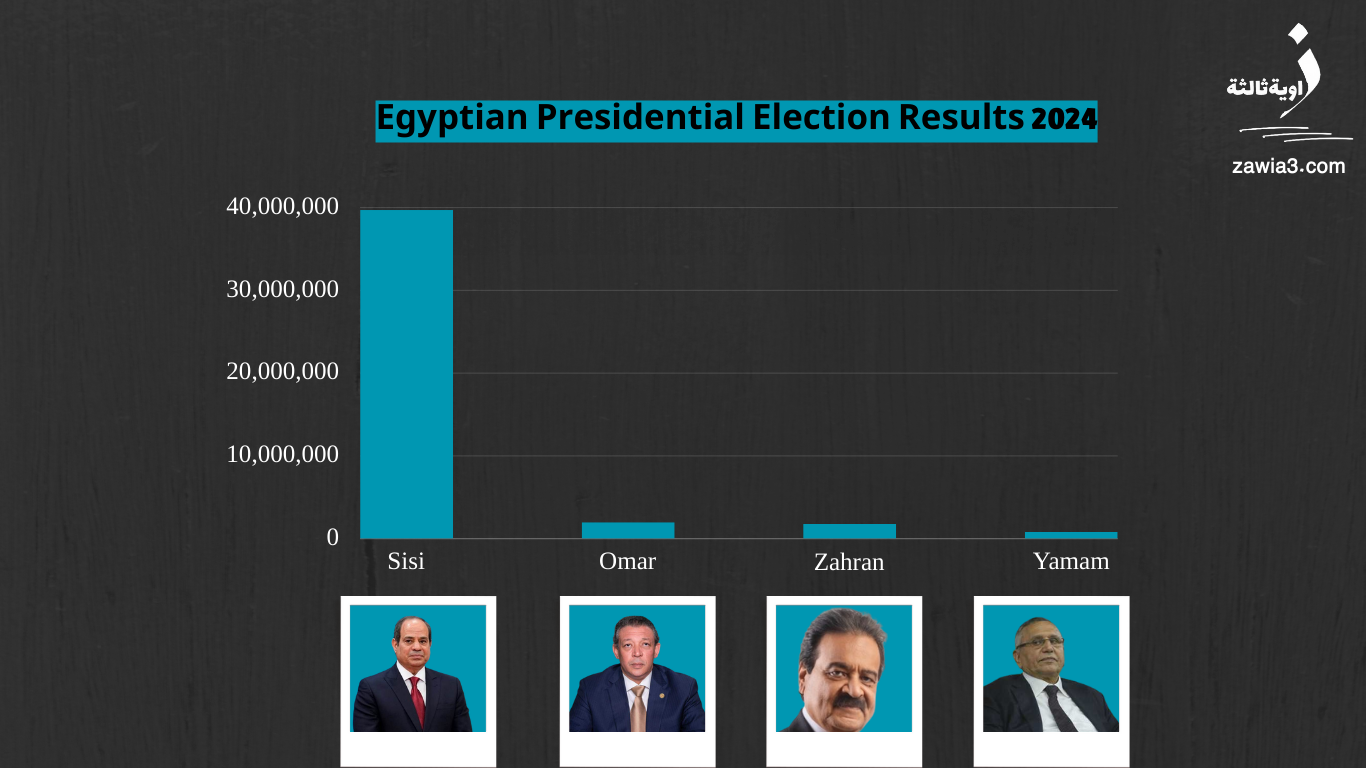

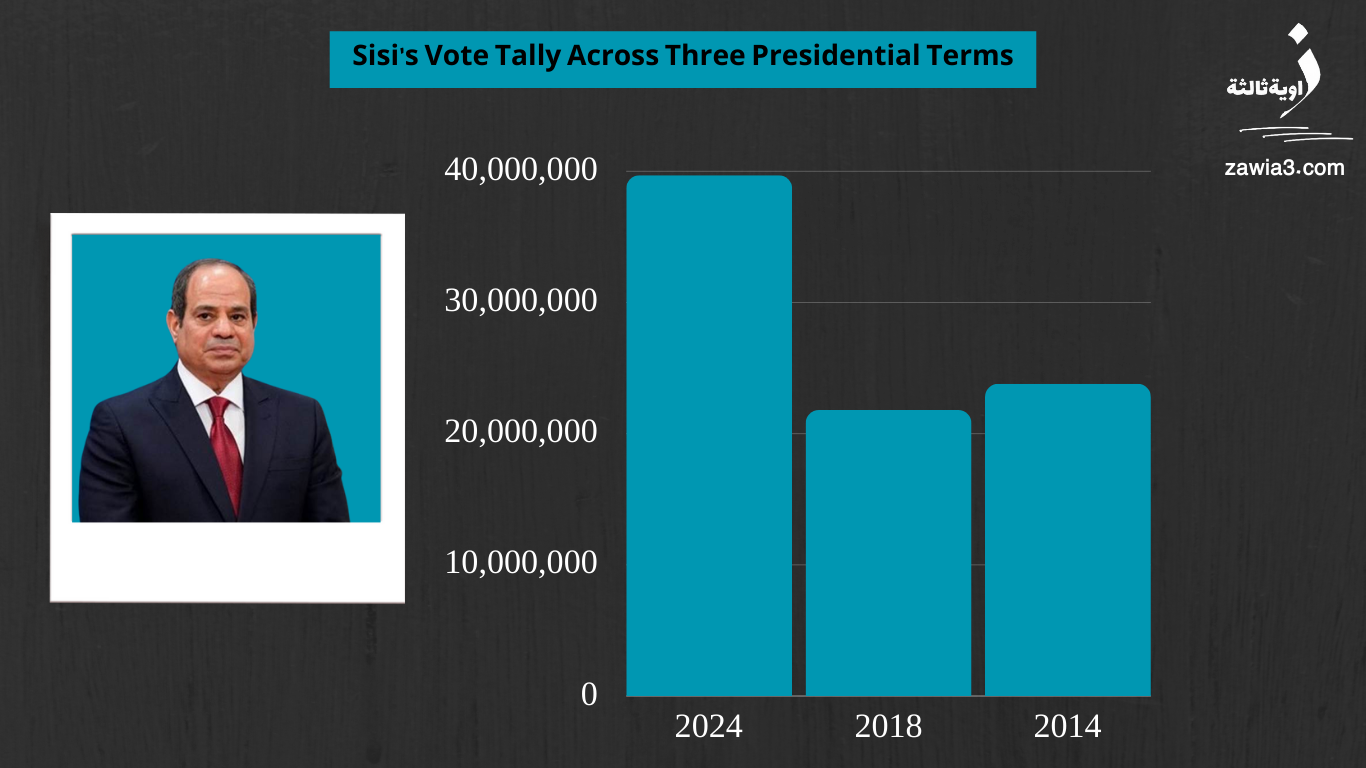

According to the announced results by the National Elections Authority, Sisi was able to secure around 39.7 million votes, with a percentage of 89.6%. His competitors, Farid Zahran, received about 1.779 million votes (4%), Hazem Omar received about 1.986 million votes (4.5%), and finally, Abdel Sattar Yemama received approximately 822,000 votes (1.9%). The voter turnout was 66.8%, with the presence of approximately 44.777 million voters out of a total registered number of around 67.032 million voters. The valid votes amounted to 44.288 million, while the invalid votes represented about 489,000 votes, accounting for 1.1%. |

According to the results, Sisi obtained the highest number of votes in the current year’s presidential elections, with 39.7 million votes, compared to 23.8 million votes in his first term in 2014 and 21.8 million votes in his second term in 2018. However, the percentage of votes he received decreased to 89.6% compared to 97% in the two previous terms.

Commenting on the results, in field interviews conducted by “Zawia3” with citizens during and after the elections, Mahmoud expressed his astonishment at the end of the election season, saying, “I was not aware of an electoral race in the first place. I felt like I was living in a parallel world and only found out about the voting when I was surprised by the electricity not being cut off during the morning hours. I checked social media pages and was shocked by a video of Sheikh Ali Gomaa talking about the number of participants in the elections, claiming that nearly 45% of voters participated. With all media also reporting that around 40% participated in the first two hours of the first day of voting only.” He added that he couldn’t understand how such a large number could participate in a very short time, questioning, “How is that possible?” He believes that the Sisi regime is known for its inclination towards propaganda and painting an unrealistic picture, expecting that the regime may have successfully gathered five million citizens on the first day at most, and the 89% figure mentioned by some in polling stations since the first day might be “fabricated.”

On the other hand, Magdi thought that the regime might have indeed succeeded in attracting a large number of citizens through various means, such as mobilising all government and private sector employees by force. This includes the lists prepared earlier under the pretext of updating the population census, approximately three months before the elections. He added, “Even the numbers displayed in front of the committees cannot claim that 45 million participated; they are prearranged preparations by cooperating entities to cover the ballot boxes.”

Ibrahim recounted his experience with presidential proxies, saying, “I witnessed how some parties collected identity cards from workers and employees by force. Some were forced to go unwillingly to obtain a presidential proxy, while officials in some areas merely took pictures of ID cards and issued proxies on behalf of others.” He suggested that the regime may have already garnered 45 million votes, but without voters going to the polls, and the votes were cast on their behalf by the relevant authorities. He emphasised, “No one in my family participated in the voting for the entire three days, and in my neighbourhood, many families also did not send anyone to the polling stations.”

Najwa added, “Any elections that do not announce the results of the subcommittees and the general committees promptly and in detail are necessarily forged and pre-prepared. In front of my house in Helwan, there was an empty polling station throughout the voting days, and I saw paid elements forcing citizens to enter taxis and head to the committees.”

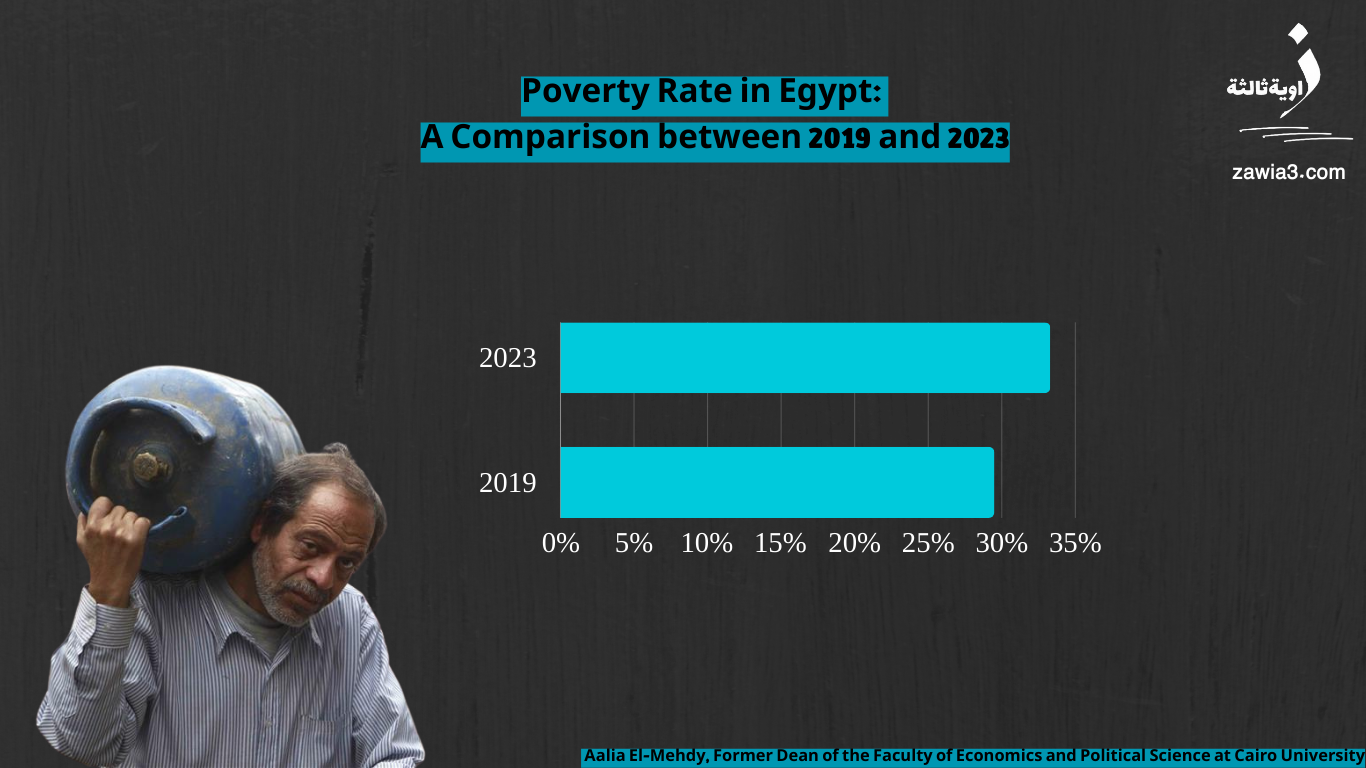

According to former Dean of the Faculty of Economics and Political Science at Cairo University, Aaliyah Al-Mahdi, nearly a third of Egypt’s population, estimated at 112 million, lives in the grip of poverty. Poverty rates were around 33.3% of the total population in 2023, compared to 29.5% in 2019. This means that approximately 37 million people are living in poverty. Unemployment rates in the third quarter of 2023 were around 7.1%, with an increase of about 94,000 unemployed individuals compared to the previous quarter, representing a 4.3% increase according to the official statistics agency. Re-electing the same regime that contributed to an increase in poverty seems illogical, especially considering public dissatisfaction with economic conditions, as revealed by a 2018 poll by the Egyptian Center for Public Opinion Research (Baseera), and subsequent data in 2019.

How did the President garner his electoral votes?

Under Law No. 198 of 2017, the National Elections Authority oversees all electoral processes in Egypt. The law grants the president the authority to appoint supervisors for all types of elections, including those in which he will run. Previously, presidential elections were regulated by Law No. 22 of 2014, which stipulated the formation of the election supervisory committee composed of the head of the Constitutional Court, the head of the Court of Cassation in Cairo, the oldest deputy heads of the Constitutional Court, the Court of Cassation, and the State Council.

According to the 2019 constitutional amendments, articles 185 and 193 granted the president the right to appoint heads of judicial bodies, control the formation of the Supreme Judicial Council, choose the public prosecutor, and control the election regulatory body, contradicting the fundamental principles of the separation of powers and judicial independence.

This move increased scepticism about the integrity of the elections, especially as President Sisi, on October 4th, made partial changes to the National Elections Authority after a presidential decree appointed five new advisors to its presidency and membership, just two days after announcing his intention to run for re-election.

Firstly,Zawia3 conducted field interviews with 600 citizens in 38 neighbourhoods of Cairo before the start of the election process between September 20 and October 30. About 400 citizens, representing 66.6% of the sample, gave testimonies about police forces, individuals, or party-affiliated organisations associated with the authorities forcing them to surrender their national ID cards or a copy. The majority of them were aged 20-55 and worked in informal occupations related to the street (tuk-tuk drivers, street vendors, cafe workers, fast-food servers, garage workers). Their testimonies ranged from “summons by the police” to being forced to hand over their IDs, collecting between 10-20 IDs per person within a maximum period of seven days, without compensation.

Said (a pseudonym working as a garage guard in the Helwan district south of Cairo) claimed to have collected 100 ID cards on his own and handed them over to the police department before the announcement of the candidacy period, receiving no payment in return. He mentioned targeting all the drivers who rented spaces in the garage and their relatives.

However, (33.4% of the sample), mostly women who were non-working housewives or daily wage domestic workers, denied receiving any directives regarding ID collection.

According to various social media applications, during the election preparation and management period, coordinated efforts to mobilise votes for Sisi were observed. The methods included threats, coercion, and financial incentives ranging from 200-300 Egyptian pounds per day, targeting voters from lower and middle-income classes. The phenomenon of rotating queues, meaning the same people were mobilised daily but alternated between different polling stations, was also noted. Most testimonies focused on collecting personal IDs from individuals working in irregular jobs or daily wage workers, such as tuk-tuk drivers.

|

According to official statistics, the number of licensed tuk-tuks in Egypt until December 2022 was 219,900, while in 2021, the official spokesperson for the Cabinet stated that there were 2.5 million unlicensed tuk-tuks. A representative of the General Association of Tuk-Tuk Owners in the same year claimed there were around 5.4 million unlicensed tuk-tuks. Assuming that 5 million tuk-tuks are each driven by two drivers, there would be 10 million IDs, presumably gathered or mobilised for the elections. By the same measure, and according to official statistics in 2019, there are 2 million cafes in Egypt, with an average of three workers in each, totaling 6 million workers. Assuming they were also compelled to submit their IDs, we have 6 million workers who either provided a copy of their ID or participated in the elections. Data from the Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics indicates that the number of available garages in Egypt was 435.4 thousand in 2017, each employing at least one worker. |

Social Solidarity officials issued directives to registered workers under the category of “irregular employment” to quickly head to polling stations. Preceding this, proxies were prepared under the threat of discontinuing the monthly assistance provided by the ministry. The official registered number of these irregular workers is 1,066,873.

Secondly, government and public sector employees, representing 20% of the employed population at the national level (27.9 million in 2022), with government employees numbering 5.5 million according to official statistics.

Thirdly, beneficiaries of the social solidarity system and aid provided by the Ministry of Solidarity, especially the Takaful and Krama program, amounting to 22 million citizens in 2023.

In conclusion, based on the observed electoral process and the data collected over two months, Zawia3 attempted to document several testimonies and present a hypothesis on how votes were mobilised. Assuming that these groups were forced to participate, their total represents about 44 million citizens (10 million drivers of vehicles and tuk-tuks, about 6 million cafe and service workers, around 435,000 garage workers, approximately 1.066 million irregular formal workers, 5.5 million government employees, and around 22 million beneficiaries of the Takaful and Karam program).

Why do we assume that the announced attendance figures are not accurate?

For two reasons: first, as published by “Zawia3” on December 10th under the title “Cash-Driven Votes: Unmasking Election Tactics in Egypt,” the system has been shown to use various means to mobilise voters or their personal identification cards.

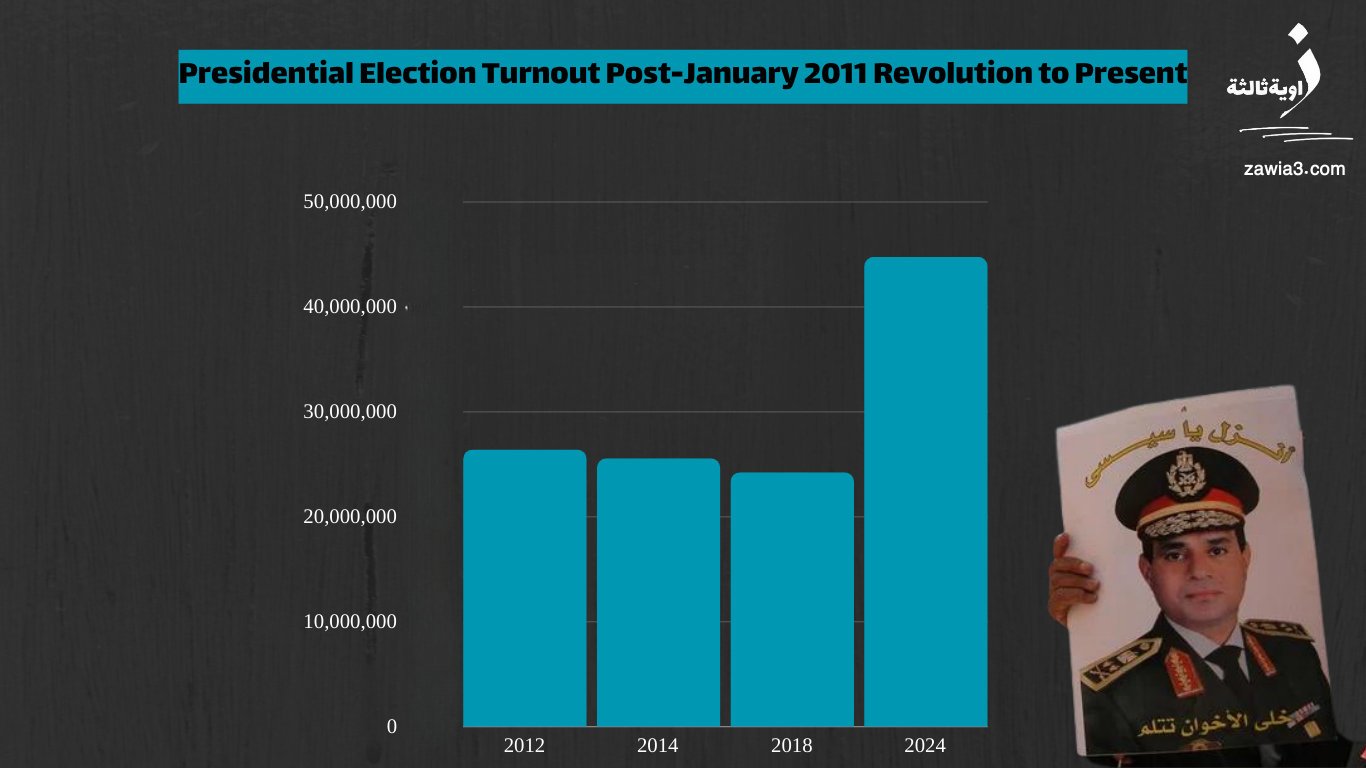

Second, in the 2012 Egyptian presidential elections following the January revolution, considered by many Egyptians as the first democratic electoral experience in the country, the Muslim Brotherhood intensified its efforts to support its candidate, Mohammed Morsi. Supporters of Hosni Mubarak and state-affiliated forces provided full support to candidate Ahmed Shafik. Simultaneously, leftist forces supported Hamdeen Sabahi, and various trends endorsed other candidates, including Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh. Despite all these efforts and significant competition, the number of participants in these elections did not exceed 23,672,236 Egyptians. In contrast, in the 2024 elections, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi received a total of votes surpassing all post-January revolution election participation numbers, reaching 39,720,000 out of a total of 44,777,685 voters, representing an approval rate of 89.6%. This led us to question the accuracy of the announced figures.

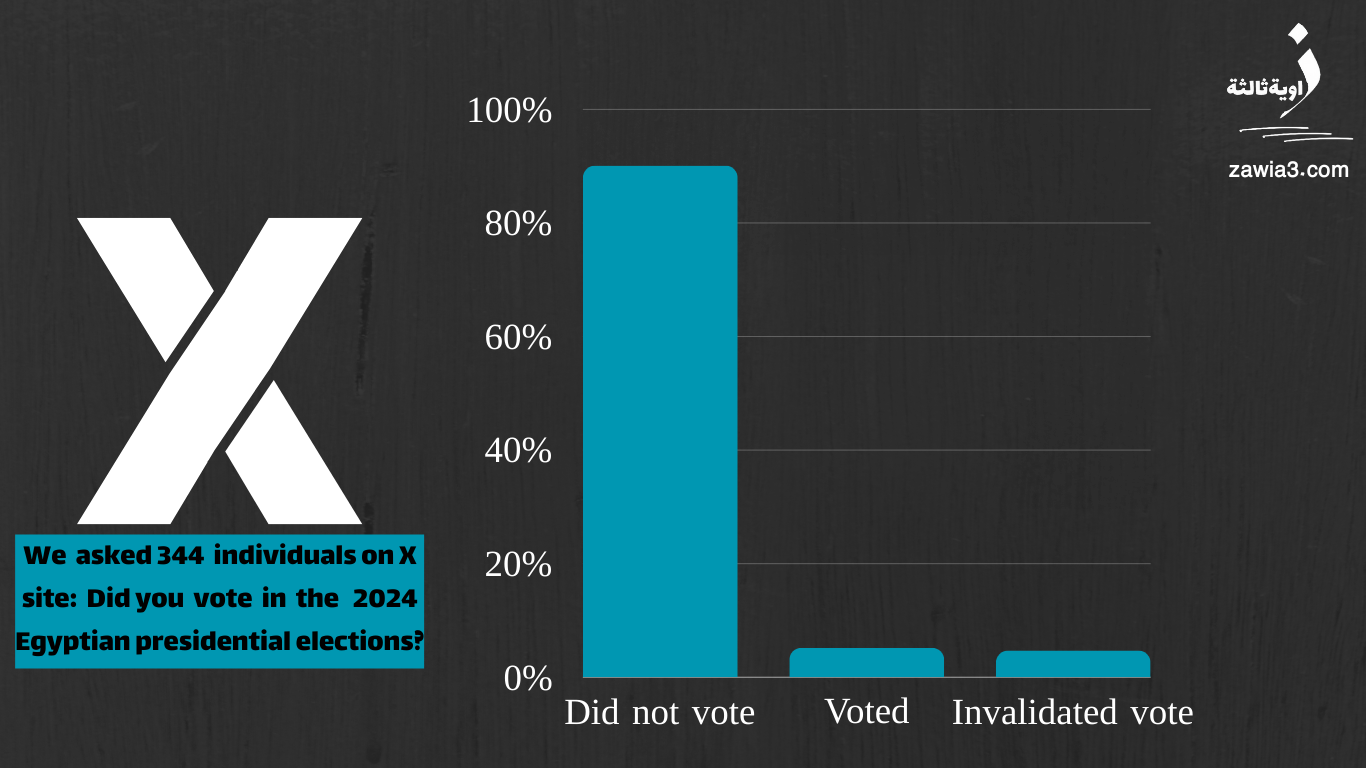

This prompted us to conduct a vote to measure the extent of participation in the previous Egyptian presidential elections, and we conducted the voting through the social media platform “X” on December 19th. The voting included 344 participants to gauge citizens’ interaction with the electoral process.

The referendum results showed that 90.1% of the participants did not exercise their voting rights. In contrast, 5.2% of the participants claimed they participated in the elections, while 4.7% said they decided to invalidate their votes.

Although “X” website users do not represent the entire Egyptian population, they constitute a significant percentage. The latest figures published in the site’s advertising resources indicated that it has 5.80 million users in Egypt at the beginning of 2023.

In addition, the announced numbers of participants in the 2024 presidential elections are clearly contradicted by a field study conducted by the Egyptian Center for Public Opinion Research “Baseera” (Informed Politics) after Sisi’s first presidential term, specifically in 2016. The study found that the President’s popularity had dropped to 68%, compared to an 82% satisfaction rate just two months earlier. This decline occurred due to rising prices, impacting Egyptians. In 2023, the prices of essential goods in Egypt rose unprecedentedly, and the Egyptian government failed to reduce prices as promised. In October of last year, Prime Minister Mostafa Madboly held a meeting with officials to monitor the availability of food commodities in markets and control prices. They agreed on the necessity of implementing radical solutions to ensure a reduction in the prices of essential goods to alleviate the burden on citizens. Subsequently, they announced the launch of an initiative to reduce the prices of essential goods by percentages ranging from 15% to 25%. Members of the parliament, however, stated that the prices of essential goods continue to increase, despite Prime Minister Madboly’s initiative, pointing to their ongoing efforts to implement the initiative seriously. A member of the Human Rights Committee in the Parliament, Mahmoud Essam, commented on the government’s initiative, stating, “The prices of essential goods such as poultry, meat, rice, and sugar included in the initiative have not decreased but have witnessed continuous increases since the initiative was launched.” Additionally, there have been unprecedented crises in the rise of prices of basic commodities such as sugar and onions, essentials in the Egyptian kitchen.

According to a recent study conducted by researcher Marwa Lashin, the negativity and lack of political awareness among the majority of Egyptians are high. Egyptians prefer not to discuss political matters for fear of exposure to risks, focusing their conversations on questions about bread, rationed goods, and other issues related to social assistance, dignity, and means of living. The researcher points out that despite the increase in political parties after the January 2011 revolution, they represent only 2.2% of the social participation of youth, with party participants constituting 0.12% of the total youth population in the age group of 18-29, which represents about 21.9 million people, 21% of the total population in January of the past year. They are actually less than half of those listed on the electoral rolls, but they are not genuinely interested in political work. The researcher conducted her study on the working class in a village in rural Egypt, concluding that there are multiple reasons for their positive participation in voting since Sisi took over the country’s affairs in 2014. These reasons range from awareness of the importance of their votes to protect the country from the “Muslim Brotherhood and terrorism” to fear of the supposed fine imposed by law for those who do not participate in the voting process (according to the law, 500 Egyptian pounds, equivalent to about 16.14 US dollars), and voting in exchange for rationed goods, electoral funds, and transportation means from their homes to the polling stations. Some of them, however, refrained from participating in any electoral events since the 2011 revolution, either due to their lack of trust in political circles and deputies, knowing that their vote is “worthless,” or due to legal judgments resulting from the deterioration of their economic conditions and indebtedness, or their ignorance of the existence of an electoral event in the first place.

According to a report prepared by the Atlantic Council, an American centre specialised in providing programs for studying security, political, and economic issues, it was expected that Sisi would win without any changes, in line with the fact that the 2018 presidential elections were “fraudulent.” Sisi was re-elected with 97% of the votes amid low turnout after he competed in the elections against a single rival who was himself a supporter of Sisi. The main rival, Sami Anan, former Chief of Staff, was arrested, and the second rival, Ahmed Shafik, was placed under house arrest. The arrests led other serious candidates like human rights activist Khaled Ali to withdraw, citing harassment and intimidation. The same happened with the politician Ahmed El-Tantawi, who failed to gather the necessary endorsements for the recent elections. The constitutional amendments approved by an overwhelming majority in a national referendum in 2019 extended the presidential term to six years and abolished the maximum limit for two terms for the president to remain in office. The amendments paved the way for Sisi to run for a third term lasting six years and stay in power until 2030. This means that Sisi will remain in office even if no one elects him.

This trend is supported by election laws researcher Sayed Abu Ela, who has been monitoring Egyptian elections since 1995. Speaking to “Zawia3” regarding the attendance rate, he said: “It is impossible for those numbers to be accurate in any case. According to the observation of the Egyptian street during election days, it was almost empty, and Egyptians considered voting days as holidays spent at home. There is a well-known rule for election observers that participation numbers can be expected based on the number of participants in the candidate’s campaign. For example, if the number of participants in Sisi’s campaign is a million people nationwide, then the number of voters would be ten times that, meaning that the participants in the electoral process would not exceed 10 million citizens.” He emphasised that there were no genuine elections, and most Egyptians boycotted those elections for two reasons: first, the regime prevented the existence of genuine candidates who were not supportive of its regime, meaning the end of the electoral process in its infancy, as elections should be between a number of different candidates and not between candidates who support one participating candidate. The second reason, according to him, is the escalation of the extermination war on Gaza, which increased Egyptians’ aversion to participating in elections amid the destruction of a neighbouring and brotherly people. This made them feel ashamed if they turned away from supporting Gaza to internal affairs. Adding, “A significant portion of those present in the presidential elections are public and private sector employees whom security agencies forced to participate in the elections.”

|

Note: Zawia3 documented in the report published in Arabic a video of an Egyptian tuk-tuk driver in one of the neighbourhoods of Cairo, stating that security instructed him to bring 10 IDs and that he would receive 150 Egyptian pounds for each ID. We also documented a video of two women in front of the polling stations in Helwan, Cairo. The first woman says she is voting in the elections because she knows she wants to be safe when completing official documents, while the second woman said, “I am here, and everyone is here because they told us we must do so. In any case, we all know that Sisi will succeed, and we, as citizens, are just a staged and illusory appearance to embellish the image. The truth is that everyone dislikes Sisi”. We hid everyone’s faces to protect them from security implications. |